Launching in May, the UK Digital Twin Center is on a mission to democratize digital twin technology.

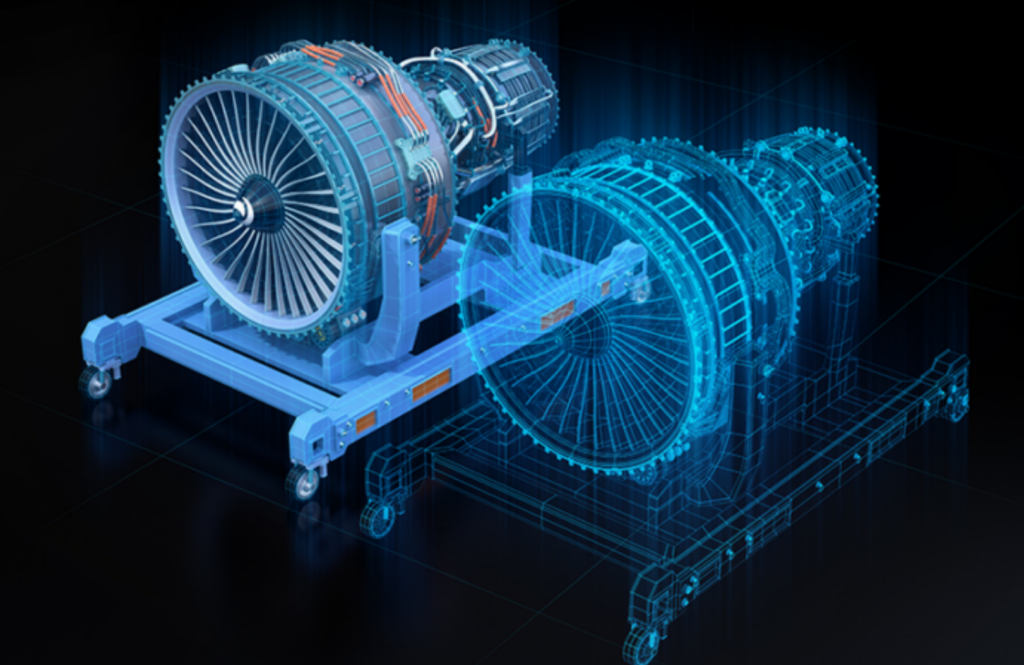

Digital twins have been around for decades. But so far, the technology has been mostly available to big manufacturers in major industries such as the automotive and aerospace. Without large-scale funds and resources, smaller companies may be missing out on the benefits of digital twins.

A new UK research center wants to change that.

The UK Digital Twin Center aims to develop a digital twin sandbox—a set of reusable templates, standards and methodologies—to give more engineering firms access to digital twins. Being able to design, test and fine-tune products in the virtual world will enable companies to shorten development times, reduce development cost and even lower the carbon footprint of their technology projects.

“We want to create a competitive advantage for those smaller businesses by giving them the ability to design, diversify or enhance a product in the digital world without having to go through all the prototyping, iterations and physical building,” Deborah Colville, director of the UK Digital Twin Center, told Engineering.com. “We want to create a path for them to adopt digital twin technology in a way that is less costly and less complex.”

The UK Digital Twin Center will open in May 2025 in Belfast, Northern Ireland, having secured £40 million in funding from the UK government and commercial partners including the defense conglomerate Thales, maritime tech company Artemis Technologies and aerospace firm Spirit AeroSystems.

Here’s how the Center plans to spread digital twin technology—and why even big companies should be interested.

Not starting from scratch

The Center’s goal of a digital twin sandbox would allow companies to create bespoke solutions without having to start from scratch every single time. The idea, Colville thinks, could be game-changing. Being able to build new digital twins by reusing previously developed and perfected subsystems and components would enable the Center to cut down the cost and complexity of each project. The resulting “digital twin as a service” offering would be affordable to a wide range of companies.

“The problem right now is that digital twins are being built for one particular problem and nothing is repeatable,” said Colville. “They are not reusable, and that’s something that needs to be solved.”

The throw-away nature of digital twin solutions is a costly luxury that many smaller companies cannot afford. On top of that, a plethora of disparate systems and technologies must come together to produce a functional digital twin, adding engineering challenges. These systems, Colville says, are usually not designed to work together seamlessly from the get-go, and protocols and standards for their easy integration are, so far, missing.

For example, Colville explained, building a digital twin of a factory production line might require integrating legacy data collection systems such as SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition), with state-of-the-art IoT data collection, AI, cybersecurity systems and immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality.

“This integration process can be costly,” Colville said. “These components need to be integrated with advanced algorithms capable of performing tasks like fault detection, performance optimization and predictive maintenance. It requires significant engineering effort, and because much of this work is bespoke, it cannot easily be reused across projects.”

The digital twin as a service would take care of those pesky tasks, allowing clients to just define the problem and have a complete solution build using the developed and pre-tested sandbox.

Building it up

The UK Digital Twin Centre has begun developing templates for this sandbox through demonstrations involving different industries and types of problems. Artemis Technologies, known for developing zero emission ships, is building a twin of a carbon neutral vessel for the servicing of offshore wind farms. The company hopes that testing out aspects of its designs, including engine efficiency and safety, in the virtual world will help speed up development and reduce the cost of meeting regulatory requirements.

European aerospace giant Thales is going to develop standardized scalable frameworks which could form the basis of the digital twin sandbox. Colville said the project should result in the first ever reusable digital twin methodology.

Spirit Aerosystems, which makes aerostructures for commercial airplanes, is working on a digital twin of a jet engine thrust reverser, a component that helps an aircraft decelerate after touchdown. The goal is to reduce the development time and cut cost by slashing the number of physical prototypes needed in the process. Colville estimates aerospace companies may be able to reduce development times by up to 18 months when making new designs of vital parts, such as aircraft wings, using digital twins.

“These use cases will inform the design of the prototyping and experimentation environment, ensuring it addresses the most pressing technical, operational, and business needs,” said Colville. “The use cases will allow architects and engineers to rapidly test and evaluate vendor solutions in realistic scenarios, validate assumptions, explore integration challenges and assess performance.”

The technologies developed and lessons learned from the initial use cases will form the basis of the digital twin service the Center envisions. By gradually building up evidence, the Center hopes to foster the case for risk-free adoption and attract more investment.

“We will be constantly learning from the experience of these companies,” Colville said. “This way, we will build up real-world experience in building digital twin technologies in a range of different scenarios. This real-life learning will inform our diffusion programs that we want to offer to the wider industry to start building their capabilities as well.”

A bright future

The Center plans to enter agreements with major vendors of digital twin technologies in the hope to facilitate the development of open standards. Agreeing on general rules would enable the creation of a flexible environment where different technologies could coexist and complement each other.

“We are not going to be a shop for one particular vendor or platform,” says Colville. “We want to facilitate different vendors talking to each other to allow different technologies to come together.”

The Center is being opened at an exciting time, when fast advances in AI are reshaping many fields of human activities. Colville expects the digital twin sandbox will benefit from the gradual integration of these advances, leading to the development of intelligent digital twins that will unlock a whole new range of applications and opportunities in other industries than those traditionally associated with the use of digital twins. For example, complex twins, including those of the human body, will be made possible through real-time synchronization with their physical alternatives and constant incorporation of data from the surrounding environment.

“There are certain things that need to be unlocked going forward,” Colville said. “Once that’s done, we see a great potential in areas such as pharmaceuticals, energy, but even things like personalized healthcare. That’s definitely something we see ourselves moving into in the future.”